Actions to take: Make no immediate changes as a new manager. Wait to implement changes until you have established a rich understanding of each of your employees, and they understand who you are as a manager. A rough rule of thumb is three months. During that time, spend your energy on developing those understandings. Write down any change ideas you have for later review.

Its your second day as manager, and you can already tell some things need to change. Maybe you were promoted internally. You've been around for years and seen the cracks developing thanks to a series of weak bosses. Maybe you were specifically brought in to "clean up the mess" in this department. They warned you during the interview process that this team needed to be whipped into shape.

Or maybe it's more mundane than that. You just see a few fixes that will make everyone's work easier.

Whatever the situation, you need to wait. Do not make any immediate changes as a new manager. After referencing this advice in the Transition Costs article, I realized that we hadn't covered this important topic. If you are an ambitious type who wants your team to succeed, you're probably internally shouting at your screen. Wait? This will improve things! We'll work better with this change! Why should I wait!?

When you make changes as a brand new manager, you won't know what you are doing. You will think you know what you are doing. No one will tell you otherwise (part of the problem). But from both a personnel perspective and from a process perspective, you won't know what you're doing.

On the people side, you won't know who is for this change and who is against it. You will have no idea how to effectively manage your team's commitment to the change. Everyone will have reactions. If they are smart, they won't share their honest opinions with a new manager. Think about it. They've had bosses who punish them for being candid, who did not reward them for having opinions that differ from the boss's opinions. We've all had bosses like that. Until you've spent time proving that you can respect diverse opinions and reward candor, they will be smart to treat you like you don't.

On the process side, you do not know the details of your change. No matter how much you've thought about it, no matter how well this worked in other environments. You have the broad idea, but you don't have the fine-grained understanding of this environment that is necessary to effectively implement this change. Every workplace is an integrated system. Move one part, and every other part compensates in some way.

In truth, the manager never understands the whole environment well enough to anticipate exactly how a change will go. Our workplaces are too complex for that these days. It isn't your job to perfect understand every detail of the work you team does. Rather, it is your job to communicate and work with your team. It is your job to ensure that they will help you implement change by understanding the change and communicating how it will impact their work. Even the "process side" of change is really a people issue. As a team, you can effectively implement changes.

Implementing changes early on is like going into a dark cave without a light. You have no idea which step will be the one with the hole that breaks your leg. You won't even be able to predict if that leg-breaking step will come in the form of a process issue or a resistant staff member.

There is no hard line for "too soon" to make changes, but a rough rule of thumb is three months. The less defined but more accurate answer is that you can begin making changes after you know your team and they know you. That doesn't happen with one or two chats. It doesn't happen by asking how their day is going once in a while. It requires intentional effort and significant time. During that first three months, spend your energy on learning about your team and their work. (The internally promoted folks may be saying "We already know each other." Nope. They know you as a coworker, but they do not know who you are as a manager.)

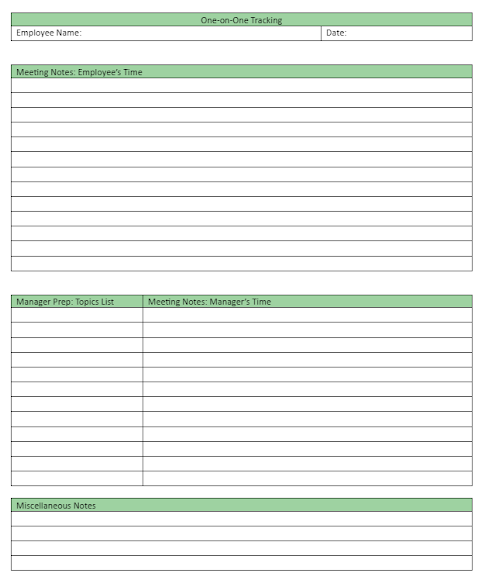

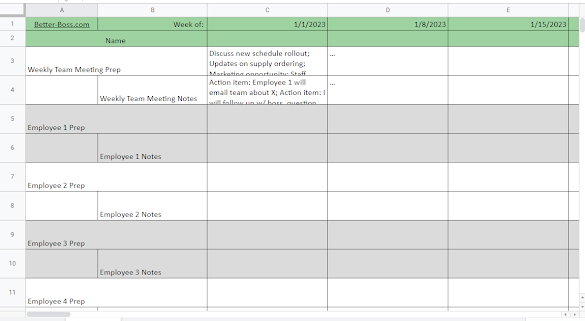

The only exception to the "no immediate changes" rule is routine one-on-one meetings. If the previous manager never did one-on-one meetings, you do not need to wait to implement them. One-on-ones are the primary way that you'll establish the understanding we are talking about here.

Think of it this way. Imagine you were hired to paint a house. First day on the job, you show up with your brushes and rollers, and the home owner says, "Oh, the last painter just used their hands. They didn't need brushes." Painting a house means applying a thin, even layer of paint to a surface. Brushes and rollers are the easiest, most efficient way to do that job. Managing people means frequent, detailed communication on a thousand different subjects. One-on-ones are the easiest, most efficient way to do that job.

Rather than making changes right out of the gate, write down your ideas for change as they come to you. After a few months, return to that document armed the knowledge you've gained about your team. You'll have a good laugh about what a disaster it would have been to make those changes in early days.